Ajahn Paññavaddho Thera

(1925 – 2004)

« My father, J.W. Morgan, and my mother, V.M. Morgan both came from South Wales in the UK. My father was a mining engineer and went out to work in South India in the Kolar Gold fields in Mysore state (now called Karnataka).

I was born in this gold mining area on the 19th of October 1925 (2468) and stayed there for about seven years after which I went to the UK for education. My primary education was at a school in Malvern Wells in the English midlands. When I left this school the second world war started and I went to a secondary school in Tonbridge Kent in the South East corner of the UK. After about a year I moved from this school because of the war and went to Cheltenham in the midlands. When I left Cheltenham I went to an electrical training college in London, called Faraday House. The war ended at about the time I left Faraday House and got my degree.

After this I spent two years in India working as an Electrical Engineer on the mines and then returned to the UK and got a job as an "application engineer" in Stafford where I stayed for about five years. I then got another job working for the Canadian Standards Association in London. Then after eighteen months I was ordained as a Samanera in London.

My Samanera ordination (pabbajja) took place in the London Buddhist Vihara which was set up by the government of Sri Lanka, and it took place on the 31st of October 1955 (2498). The uppajjhaya was Bhikkhu Kapilavaddho who had been ordained in Thailand. On the 15th of December 1955 Bhikkhu Kapilavaddho, two other Samaneras and I flew to Bangkok and went to stay in Wat Paknam. On the 27th of January 1956 (2499), the three of us were ordained as Bhikkhus with Mangalarajamuni (Luang Por Soth) as the Upajjhaya. We did not stay long in Thailand and returned to London on the 16th of July 1956 to stay in a Vihara that was set up in London by a Buddhist organisation. In due course the others all returned to lay life and I was left to look after the Vihara. I remained in England looking after the Vihara for five years, when another Bhikkhu came and took over. Then I came out to Thailand again on the 22nd of November 1961 (2504) and went to stay in Wat Cholapratan under Ajahn Panyananda. My purpose in returning to Thailand was to find and stay with a Teacher who was skilled in the ways of practising the Teaching of the Buddha. Fortunately a Thai friend took me to meet the Venerable Acariya Maha Bua who had come to Bangkok on business.

After meeting Venerable Acariya Maha Bua two or three times I asked if I may go and stay at Wat Pa Baan Taad. He accepted me and I went to stay in Wat Pa Baan Taad on the 16th of February 1963 (2506). I was re-ordained in the Dhammayuta Nikaya on the 22nd of April 1965 (2508) and I have remained in Wat Pa Baan Taad since I first came here.»

Bhikkhu Paññavaddho

Wat Pa Baan Taad

May 1999 (2542)

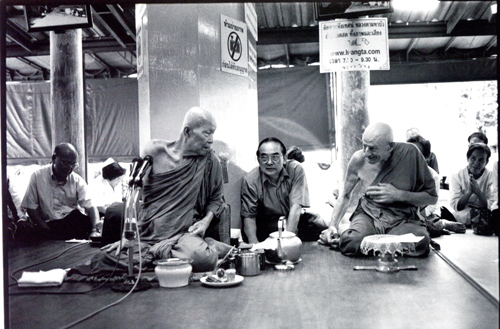

Than Ajahn Maha Bua's Eulogy of

Than Ajahn Pañña on the 18th of August, 2004

« Than Pañña is an English Bhikkhu who first came to stay at Wat Pa Baan Taad in 1963, and has been living here ever since. Not only did he develop himself to the fullest, his life was also one that greatly benefited people from all over the world. Ever since he came to stay here, he has been a source of strength and inspiration to many Buddhists from many countries who have come to see him. His presence has touched the lives of so many people over the years. This is especially true of the Western Bhikkhus who have come to Wat Pa Baan Taad since his arrival. He has always shown a selfless devotion to the task of instructing these monks. They have always relied on Than Pañña to teach them the correct way of practising Buddhism. He has been an example and a mentor to most of the Westerners who have come to Thailand to ordain as monks and follow the Buddha's Noble Path.

Than Pañña passed away on August 18th at 8:30 a.m. Wat Pa Baan Taad has benefited in so many ways from his presence. Than Pañña was a trained engineer with a very broad knowledge about all things electrical and mechanical. Whenever I asked him a question about a piece of machinery – whether it was a car, train, aeroplane or orbiting satellite – he always knew the answer. I asked him if he could construct these things himself and he replied that although he understood in principle how they worked, their construction would require a factory and a large workforce. One person could never do it all. It was a very clever answer. His knowledge of engineering gave us the impression that he must be a nuclear physicist. Because he was never at a loss when giving clear and coherent explanations, we felt that he knew everything there was to know about these matters.

Occasionally, someone's car broke down in the monastery. Than Pañña repaired it right away so the owner could drive it home. He was an expert at repairing clocks and watches, tape recorders and radios. Those in the monastery who needed help in repairing these things always turned to Than Pañña – and he never let them down. That's one reason why I say that Wat Pa Baan Taad has benefited from his presence in so many ways.

On a more profound level, Than Pañña was a great communicator. He was responsible for instructing and training all of the foreigners who have come to Wat Pa Baan Taad. In this respect, his death is a tremendous loss to our monastery. His engineering skills will not be missed nearly so much as his teaching skills. He was always the first person to receive foreign visitors, and they relied on his wisdom to guide them. His teachings on Buddhism were comprehensive and invariably correct.

Than Pañña died in a calm and peaceful manner, as befits a practising Bhikkhu. His mental condition was excellent and beyond reproach. He had truly developed a strong spiritual foundation in his heart. Of this I have no doubt. When he passed away, he went with quiet dignity. And I myself have taken full responsibility for his funeral arrangements.

Than Pañña told me that he had one regret. He said that it was a shame that Westerners, who are so clever when it comes to worldly affairs, are so stupid when it comes to spiritual ones. Even though the Buddha's Teaching is superior to everything that the world has to offer, very few Westerners make an effort to learn about it. He felt that this was their own kamma, their own misfortune. When people use their intelligence solely for material purposes, they remain ignorant of matters of real substance – spiritually they are very stupid. This he felt was their own misfortune. And he was exactly right. It is impossible to equate worldly intelligence with the wisdom of Dhamma. The kilesas are one thing, and Dhamma is another. Than Pañña told me that he wanted to see intelligent people turn away from the world and turn their attention to the practice of Buddhism. If those people would practice Buddhist meditation, they could greatly benefit the world we live in. His main regret was that so few showed an interest. He saw them as very intelligent in one way and very stupid in another.

Than Pañña possessed a very subtle and refined nature. He was beyond reproach. The whole time I knew him, I never had a reason to reprimand him – never. He was always composed and circumspect, and displayed wisdom in everything he did. His death is a loss to faithful Buddhists everywhere. »